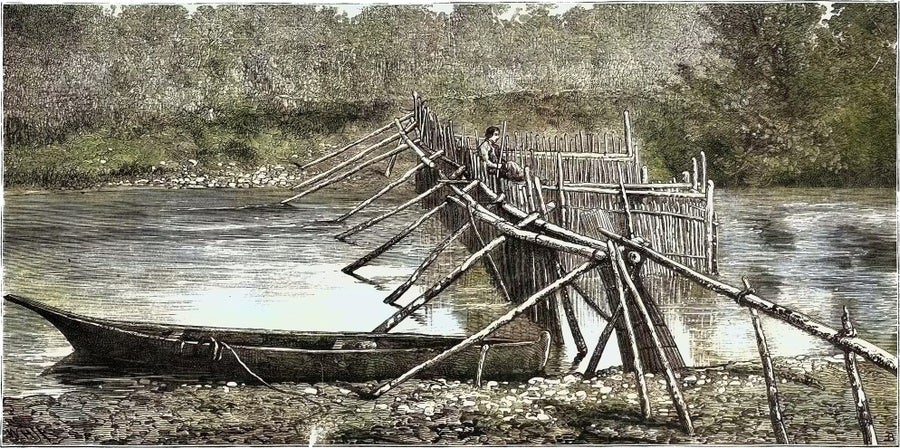

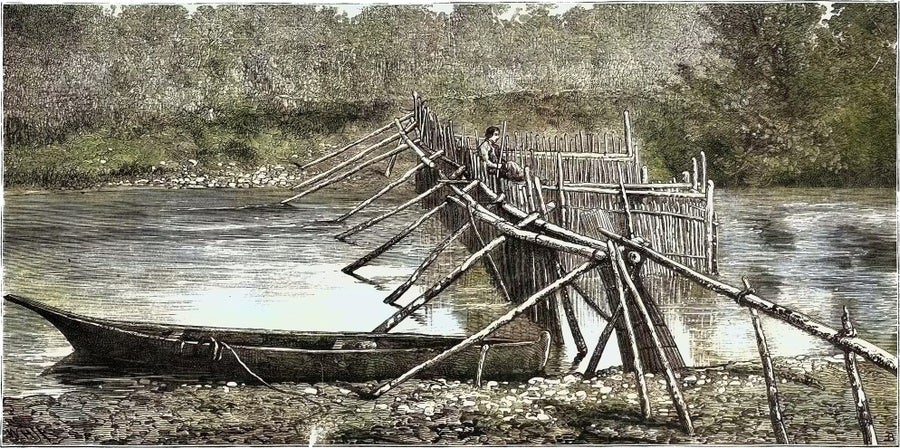

In British Columbia, Canada, the Heiltsuk nation is partnering with researchers to create new approaches to bear and salmon conservation. The article talks about several stakeholders in this conservation effort and includes an interview with the director of the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department (HIRMD). It explains the history of conservation, starting with how the Heiltsuk people would prepare the rivers for salmon migration by clearing them and scaring away predators. When industry developed in the region, bear populations declined and over harvesting led to native fish populations declining and some salmon species disappearing entirely. When regulations were finally implemented, they weren't done so from the perspective of the stakeholders that most depended on the health of the land. As the article explains, “For many decades after colonization, federal and provincial agencies controlled fishing quotas, logging operations and other resource management decisions that directly affected the Heiltsuk”. The members of HIRMD interviewed expressed cynicism about the motivation of these stakeholders, saying they made decisions for financial gain and from a place of academic privilege. This highlights the importance of considering all stakeholders and knowing their motivations behind deciding where and how to allocate funds. More recently, the Heiltsuk resource management advocates have been able to have a say in these decisions and collaborate with research projects to have access to funds while making sure modern conservation aligns better with their traditional values. They've used traditional technologies like fish traps in combination with modern ones like genotyping to survey wildlife in non-invasive ways that respect their philosophy. They've also established a land use committee to address goals like protecting grizzly bears, which as we learned will also provide secondary protection for other bear species, fish, and the environment generally. They even successfully advocated to ban trophy hunting, something that contradicts their values and was also determined to be unpopular with the general public of the region. While the scientific community and conservationist perspectives are still important to protecting wildlife, they can't be put above other stakeholders like the public and people with a cultural tie to the species. I believe that science should be incorporated into efforts led by the people most affected by conservation issues, and we need to think about different groups' motivations when deciding their level of representation in decision making.